Introduction

“The cost of inaction is far greater than the cost of action.”

Dear Reader,

What separates those of us who have achieved greatness, and did what few ever can, and regular people who do not stand out among the crowd?

Surely it cannot be that those who are great simply have a goal in mind and the rest do not. It seems that most people have dreams and ideals, yet few fulfill them.

What is the key which creates athletes, special forces soldiers and the greatest scientists? They have goals and dreams like everyone else, but they commit themselves to them no matter what, while others (the majority) choose to give up at the first hurdle or the first sign of resistance. What makes this sort of person who never gives up and strives for the things he or she wants?

It is also important to ask, can everyone achieve these same results in their desired fields or do those special few have something in their DNA?

According to ex-Royal Marine Gareth Timmins, they can. In this post, we are going to dive into Timmins’ great book, Becoming the 0.1%, which shares the mentality which got him through training in order to qualify as a British Royal Marine. The book is aptly named Becoming the 0.1% because in the UK the statistic for those who passed Royal Marine training compared to those who entered but failed was 0.1%.

Though the book itself would be too long for me to condense into any reasonable Substack post, below I will present three rules which I consider to be the most important for building the mindset that allows you to accomplish your goals. These three rules are the three which have most stuck with me and what I put into practice when I am needing some motivation.

If you put what he teaches and what I am sharing below into practice, you should be that much closer to having what it takes to become the 0.1%.

Rule 1: Never lose sight of the outcome

This is what I see as the most important of Timmins’ rules in his book. It is the most crucial aspect of never giving up. It can be too easy, when things get hard, when things are taking longer than expected to be achieved, that you lose sight of what you are working for, and you quit.

As Timmins put it:

“The reality is, regardless of how much you want something and how committed you are to achieving an aim, at some point and quite possibly on numerous occasions, you will lose sight of why you are doing something.”

It is important that you remind yourself constantly what you are aiming to achieve. Keep reminding yourself that you are doing good work, that everyone would do it if it were easy, but you are the one to take the step. It is also crucial literally to visualise what you are working toward, and picture in your mind the end result. When studying hard just imagine opening that letter and getting a full sheet of A*s (because that is what all the hard work is going into), or if on a run just imagine getting handed that Royal Marine green beret. If you give up, this dream you picture will never be a reality.

When the struggle arrives you must remind yourself that what you are doing is merely a short-term sacrifice for a long-term goal. Look further than your own nose.

In a few words: picture the one place this work will take you.

Rule 2: Remind yourself why you started

This rule can provide crucial motivation and drive when things get hard. In the very opposite way to the first rule, where you imagine the outcome of your hard work at the end so that you always stick at what goals you have in mind, you should also remember what life you hated or did not want before you began on this new course, so that you are reminded of why we decided to do things a little differently.

Maybe you were once fat so you started the gym, maybe you wanted to get into that great university so you studied hard, maybe you did not want your life’s work to be a failure so you decided to work hard to get that dream job of yours - whatever the goal, when things get hard you will loose the drive and forget why you started. While you should think about the outcome of what your hard work is going towards, as in the first rule, thinking about the life you wanted to leave behind should push you to continue the fight.

People in your old life may criticise you or say that you are bound to fail. Their words are merely the calls of your old life beckoning you back. They are the calls of mediocrity which is the graveyard where your dreams are laid to rest. Always remember the place you wanted to leave and you will want to continue your journey to the destination.

“Chipping away at the back of my mind was what people said wen I first revealed my intention to join the Royal Marines: ‘See you in a month’s time. You can’t do the Marines, no chance!’ This was a typical reaction and it strengthened my resolve to succeed: I had to dig deep and prove them all wrong.

[…] It is absolutely fundamental to engage in the regular mental exercises of positively reinforcing your rationale for why you want to achieve something. It might be preparing for an arduous endurance event, a weight-loss goal, a course (degree) to open doors of opportunity, or a significant and life-changing shift in career."

I used negativity and indirect attacks on my personality and character to fuel my motivation to continue. The fear of failure, of returning home and validating general opinion, provided such a solid anchor of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, that the notion of returning home without succeeding at my goal, was never an option. Failure, in this sense, was such a powerful ally.”

In a few words: you left the comfort zone for a reason, remember it.

Rule 3: Divide your goal into smaller ones

When a difficult goal lays ahead of me, something my father always says is: “How do you eat an elephant?” (Which is the seemingly insurmountable goal) “You divide it into lots of little bits.”

This is also exactly what Gareth Timmins recommends in his book. When he embarked on the Royal Marines Commando course, he purposefully wrote his diary in week segments and thought only about the day ahead, so that he did not have to think about conquering the whole 32 week period, which may have seemed far too daunting, but instead of tackling just the next week or day which was to come - a far more feasible objective which can give you the motivation to continue.

Similar to the first rule, we must always remember to visualise what we are undertaking shall do for us, and not the discomfort or the arduous process that we may need to undertake in order to reach it.

If we focus only on the task at hand, leaving everything else that may come out of our minds, all the while focusing on what the end result will be, we will be able to tear through whatever mission we have set for ourselves bit by bit - just like eating that elephant a mouthful at a time.

Gareth Timmins says that the unforeseen value of this method comes about like this:

“An awareness of the day method to achieving a long-term goal is crucial to success. The seemingly negligible achievement of completing each day - the unnoticed, subtle, and slight progression of acquiring your goal - is what often discourages 99.9 per cent of those who try and fail at any large endeavour to change their lives.

People want quick results and therefore lack the patience that the ‘mundane’ requires. Success on the Royal Marines Commando course requires an understanding that small, productive actions repeated daily and with ‘consistency’ over a long and sustained period, will lead you to the Green Beret, or any other goals you may have.

Therefore, during moments of disillusionment, ask yourself where you would rather be: on course to achieving something of tangible significance, or sat in a pub? I went back to my local pub after fourteen years of joining the Royal Marines. Nothing had changed, the context of the conversations remained the same… but I had!”

In a few words: complete the work bit by bit, forget the daunting whole.

In conclusion:

It is my firm belief that if you put all three, or any at all, of these rules into general practice towards whatever goals you wish to achieve, you will have a much heftier chance at success in the field, and becoming the respective 0.1%. The work will be the same but your mentality will be different - and that makes all the difference.

As I mentioned in the introduction, I often put several of these rules into practice myself. And though I am absolutely no Royal Marine, they have greatly helped me push myself a little further in the heart of the struggle.

One day I awoke and decided to go on a 5k run after having not properly run that far for years - I go now and did go to the gym then, but it was mostly weights and much shorter runs - and I vowed to myself not to stop once. Even though towards the end it felt as though my breaths counted for nothing and my lungs were on fire, I kept imagining the end goal of what my hard work could be, which was being handed a Royal Marines Green Beret (even though I do not intend to be a Royal Marine) and this somehow kept giving me the will to carry on and a short burst of energy. Thus my allegiance to rule 1.

Furthermore, I moved house in late 2024 which also meant moving gyms. Due to the hassle of moving and all the new things on my schedule, I ended up on long stints of not entering a gym for weeks, even though I had been pretty solid in attendance in my old one for a while before that. After some time thoughts kept creeping into my mind that I did not need to go to the gym, and that other men did not and their builds were not terrible, so I would be fine too. But something in me did not settle, I would often think about losing progress and remembered the reasons I began the gym: bettering myself and having the capability to protect others (and not otherwise be feeble) if I were ever needed to be. In essence, remembering the life I had before the gym: being a skinny guy who could not even bend a match if he tried, motivated me to get back in there.

Reading this book certainly helped shape me a little bit (which is what any great book should do) so I hope these rules can do the same for you.

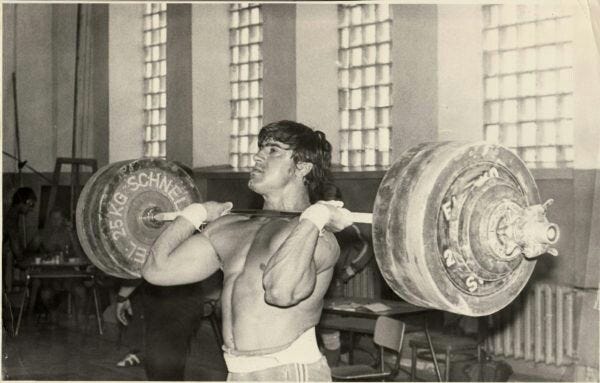

It should also go without saying that the image used for the thumbnail of this post (the man squatting about 200 kilograms) can be entirely metaphorical, as you may aim not to be able to lift heavy weights in the gym but to lift the heavy weights of study in the library so that you get into university - the same rules apply to whatever goal you have in mind.

Make sure you read Gareth Timmins full book, it goes into more detail about specific parts which arise along the path of discipline which I have not touched on here so is worth reading. Here is an Amazon link: Becoming the 0.1%

Kindest regards,

The Everything Scholar